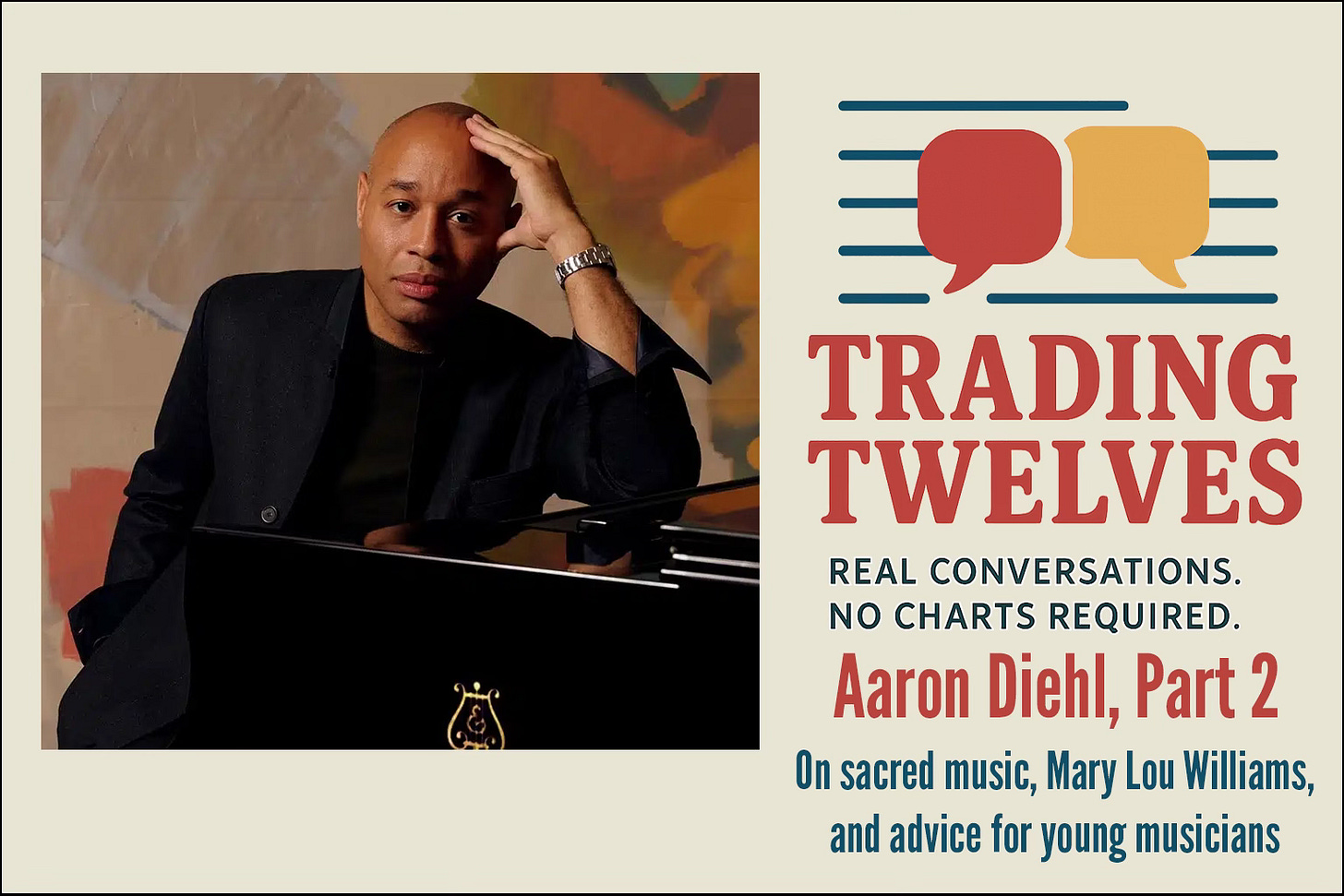

A Conversation with Aaron Diehl Part 2

Pianist Aaron Diehl discusses the music of Mary Lou Williams.

In Part 1, Aaron Diehl shared how his grandfather’s influence and mentors like Mark Flugge and Marcus Roberts shaped his path from classical training to jazz improvisation. Here, we continue our conversation, turning to his work with Mary Lou Williams’ Zodiac Suite, the composers who have deepened his artistry over time, and his perspective on what youn…