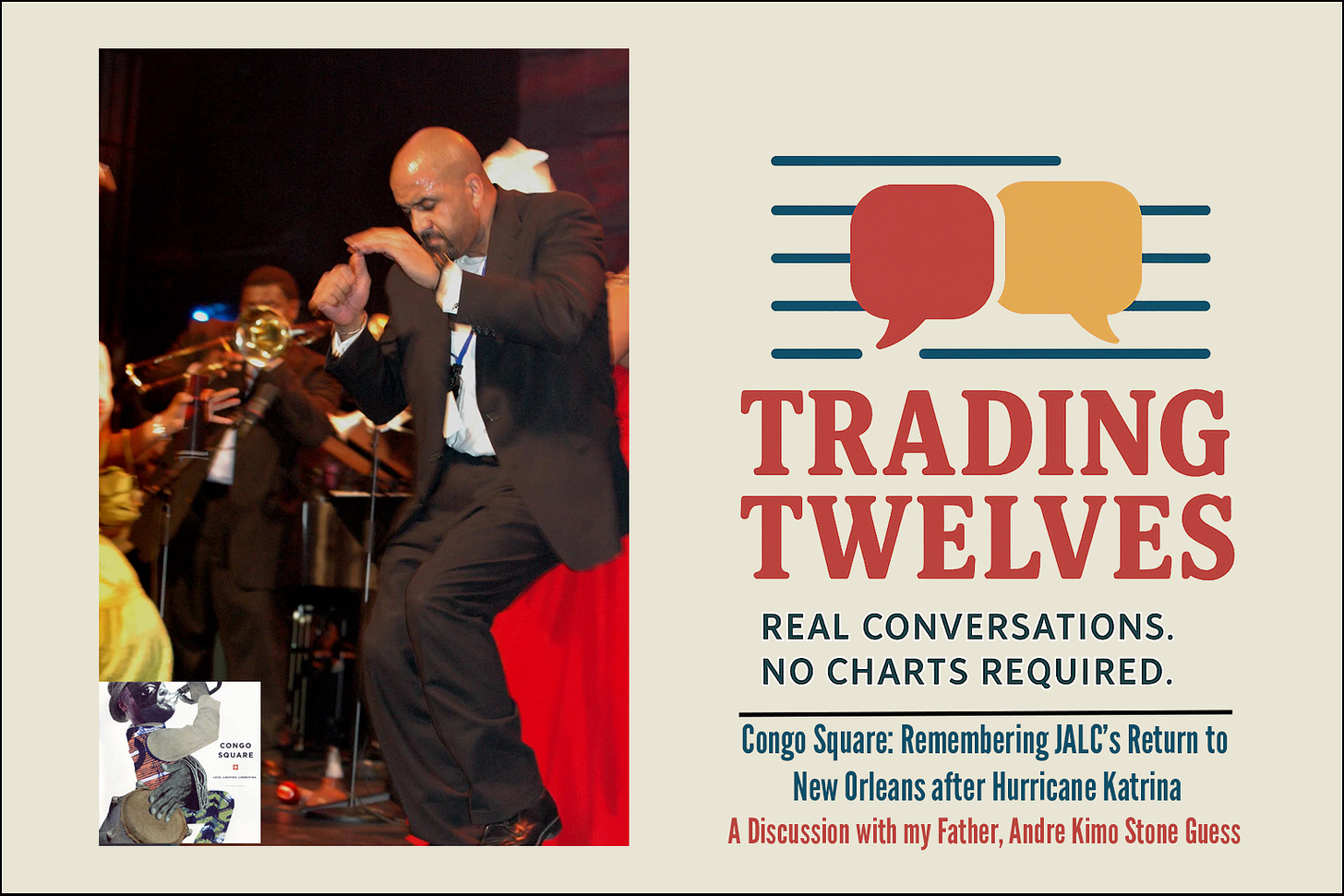

Congo Square: Remembering Jazz at Lincoln Center's Return to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina

Andre Kimo Stone Guess on producing the Congo Square concert, the first major musical event in New Orleans after Katrina.

In my previous post, the interview focused on telling the story of the Higher Ground benefit concert, which raised millions of dollars for New Orleans musicians in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Following this, the focus of Jazz at Lincoln Center shifted from raising money to a return to New Orleans. Six months after the storm, on April 23, 2006, that h…