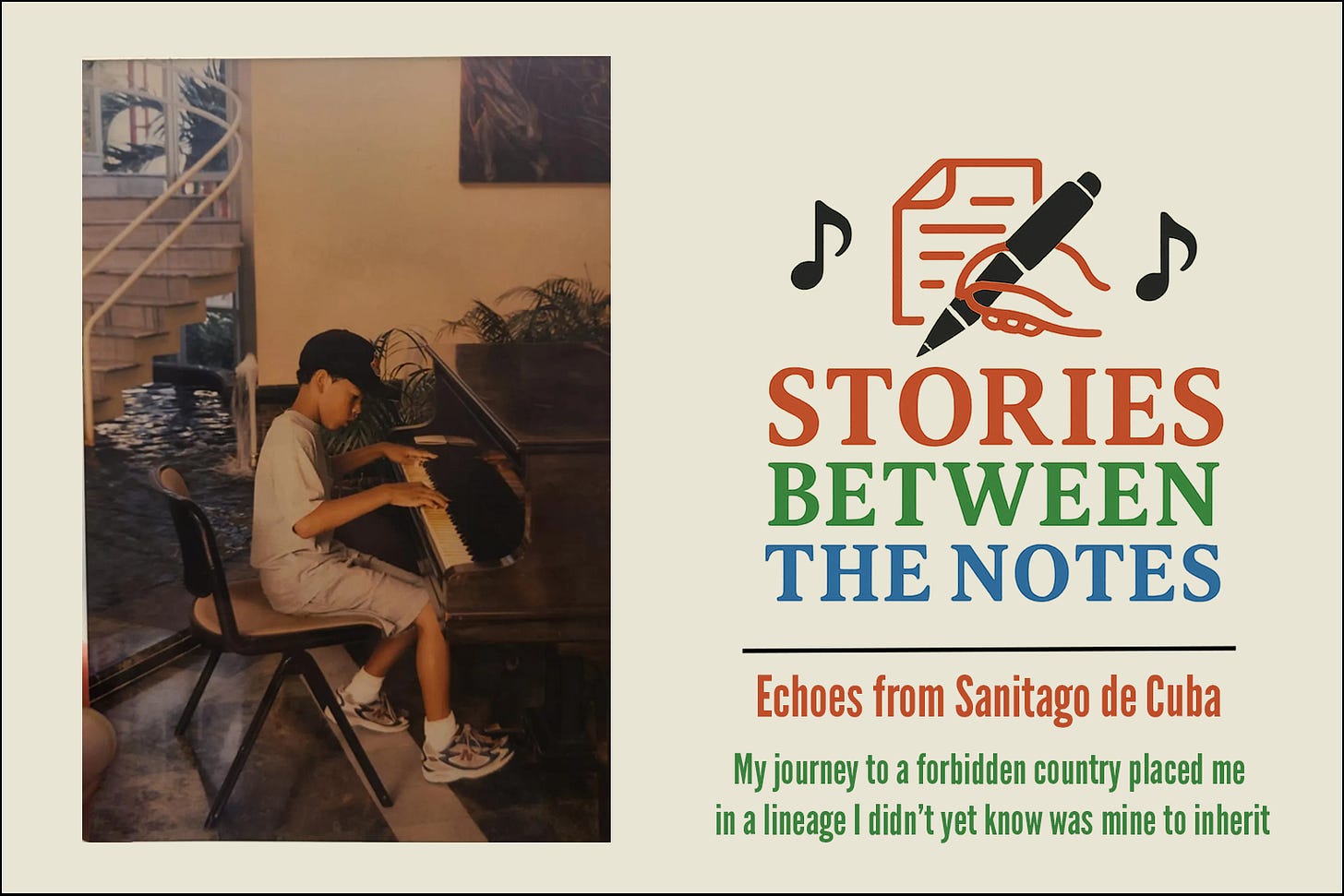

Echoes from Santiago de Cuba

My journey to a forbidden country placed me in a lineage I didn't yet know was mine to inherit

Back in 2001, my dad went to Havana, Cuba with his friend and photographer Frank Stewart to lay the groundwork for the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra to perform in the country. This would materialize in the form of a five-day residency in Havana in 2010 resulting in their album “Live in Cuba”.

When my dad returned from the trip he came back bearing all…