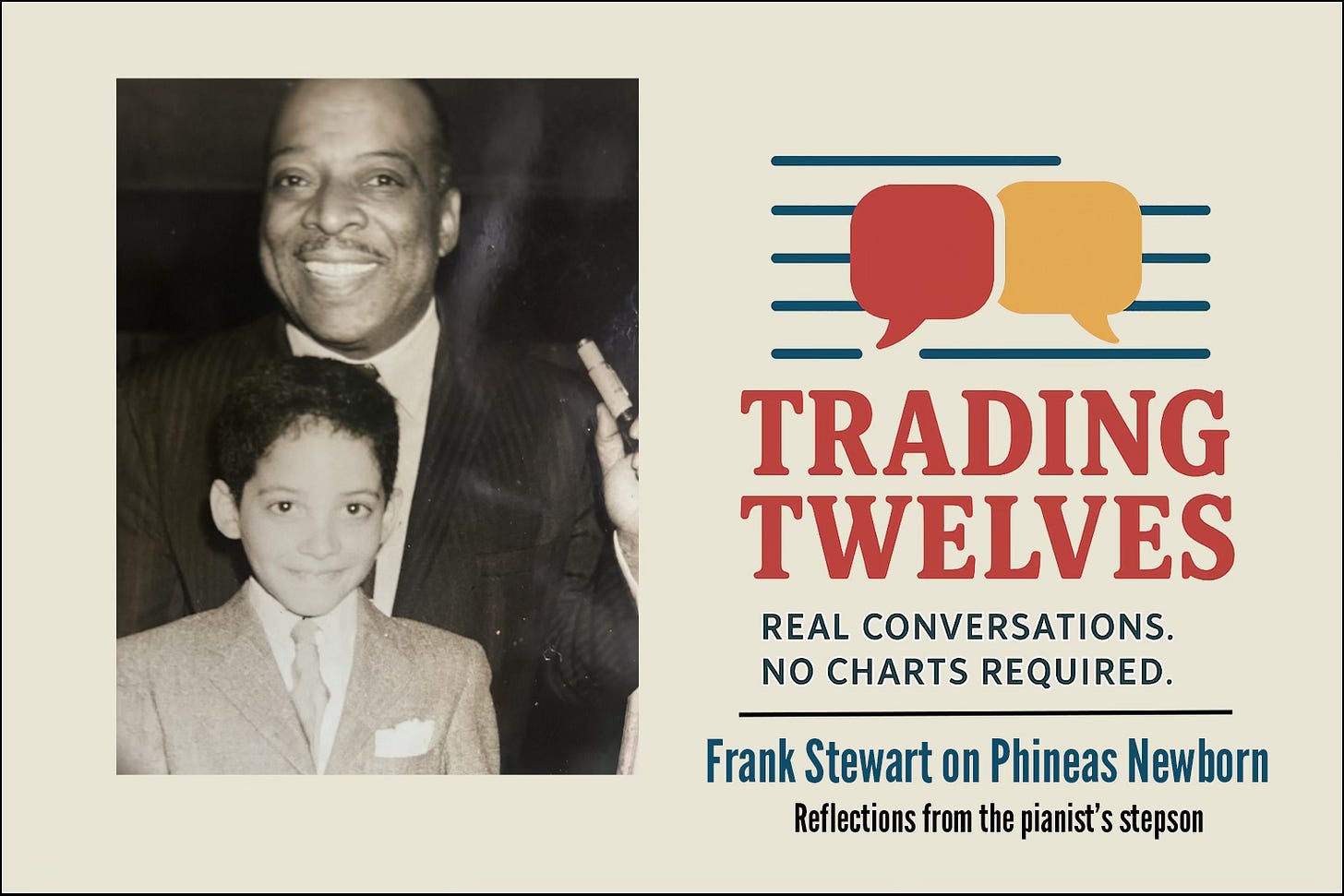

Frank Stewart on Phineas Newborn

Reflections from the pianist's stepson

In a recent post, I reflected on first hearing the pianist Phineas Newborn Jr. on a childhood road trip. That trip culminated in an exhibition of photographs by Frank Stewart at the Smithsonian, who, it turns out, is Newborn’s stepson.

Stewart, one of the foremost photographers of jazz and of black American culture, possesses a unique perspective on the …