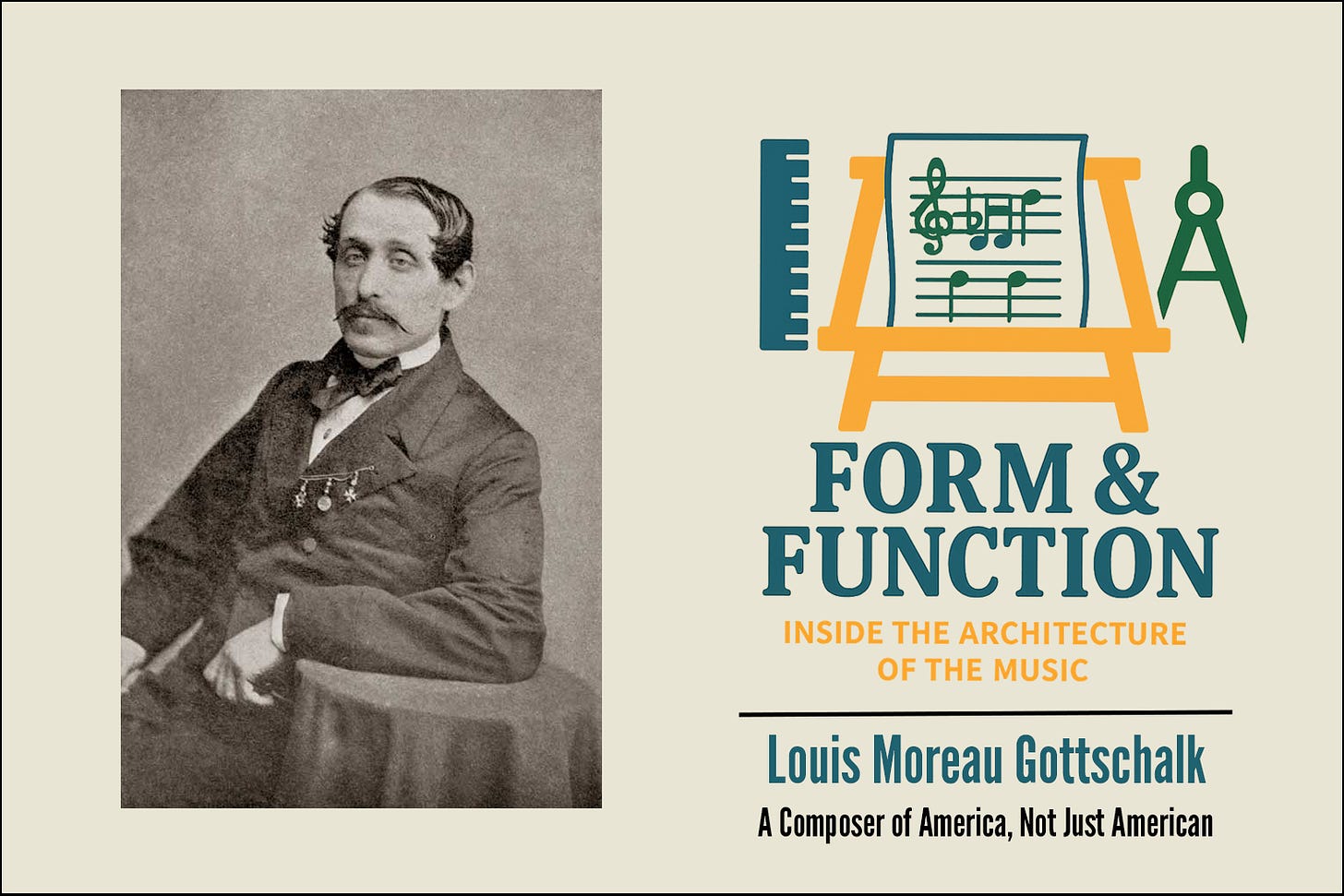

Louis Moreau Gottschalk: A Composer of America, Not Just American

From Congo Square to the Caribbean, Gottschalk reminds us that America has always been connected.

We Americans aren’t known as the most worldly people, despite the globe-spanning reach of our culture. So much of that comes from our worldview, the sense that the United States sits at the center of everything. Even something as simple as how we divide the continents reveals this bias. From our perspective, North and South America are separate continents. But in many other countries, it’s all one America. Small differences like this change how we see ourselves, and how others see us.

That tension, between insularity and connection, is part of our story. And nowhere is it clearer than in New Orleans. The city is both the cultural capital of the South and the northernmost port of the Caribbean. It has always been a crossroads, a place where worlds meet. When we think of musicians from New Orleans, we usually jump straight to the twentieth century: Jelly Roll Morton, Buddy Bolden, Louis Armstrong. But decades before them, there was another figure who embodied the city’s cosmopolitanism: Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

Gottschalk was a pianist whose talent for music brought him across nations and cultures, from New Orleans to Paris, from Puerto Rico and Cuba to Brazil, where he passed away in 1869. He was a composer that could truly be described as Pan American, and much of this can be attributed to his upbringing in New Orleans. Born to a French Creole mother and a British Jewish immigrant father, Gottschalk was exposed early on to European Classical music excelling at the piano from an early age, becoming a child prodigy virtuoso by the age of 11.

Now imagine someone with the pianistic ability of Franz Liszt, being born in New Orleans, where the African drumming of Congo Square, Classical music, and the wider traditions of music from the Caribbean were all present in the cultural fabric. You have the recipe for a very unique performer. When giving his first public performance in Paris at the age of 16, Frederic Chopin was in attendance, and reportedly offered the praise, “Give me your hand, my child; I predict that you will become the king of pianists.”

Gottschalk spent much of his life giving public performances touring the United States, the Caribbean, Central and South America and his compositions reflect this. In his piano pieces one can hear echoes of the rich music traditions that would develop across the Americas. One striking piece from his stay in Brazil was his Grande Triumphal Fantasy on the Brazilian National Anthem, written for Princess Imperial Isabel of Brazil. He dedicated its orchestral counterpart the Brazilian Solemn March to her father Emperor Pedro II.

In Souvenir de la Havane Gottschalk brings the habanera rhythm together with the stylistic trappings of a Chopin mazurka. In this context, this piece anticipates what Jelly Roll Morton would call “the spanish tinge”, something he considered an important component of jazz.

“Of course you gotta have these tinges of Spanish in it in order to play real good jazz. Jazz has the foundation that must be very prominent, especially with the bass section in order to give a great background”

If one listens closely to Jelly Roll Morton’s full explanation of the “Spanish tinge” and how it works in jazz, it becomes clear that he connects the feel of New Orleans bass rhythms, also prominent in New Orleans second line drumming, with the habanera rhythm dubbing it the “Spanish tinge” in jazz.

The piece Bamboula op. 2, refers to an African rooted dance that Gottschalk would have heard in Congo Square during his youth, while the melody is derived from Louisiana Creole folk songs. The drumming associated with the bamboula in Congo Square also shares its roots with Haitian drumming. If one listens closely, its almost uncanny how well the Gottschalk piece lines up with the rhythms of the Haitian “bamboule”.

One of Gottschalk’s most well known pieces, The Banjo op. 15, may not sound like modern banjo playing to our ears today. But the influence becomes clear when one hears the modern version of the banjo’s ancestor, the akonting which still exists in West Africa today. The banjo’s African roots can still be heard today in instruments like the akonting and one can see similarities between the rhythms of akonting playing and Gottschalk’s piece.

The life of Louis Moreau Gottschalk reminds us as Americans how connected we have always been to the wider world. Like Gottschalk, we come from a creole of different cultures and worldviews that can often come into conflict with one another. During his lifetime, Gottschalk believed that music could transcend political boundaries. His willingness to play for both Confederate and Union audiences raised eyebrows amongst some people. It makes sense that a man from New Orleans with European, African and Caribbean roots in his family would see beyond these artificial boundaries we place between ourselves. Gottschalk wasn’t just an American composer. He was a composer of America.

Excellent feature, young Mr. Wynton!

Interesting article. I like the way you connect him within the New Orleans tradition. I've always loved Gottschalk.

Totally agree about the akonting. The early (1850s era) banjo is a very similar sound too.