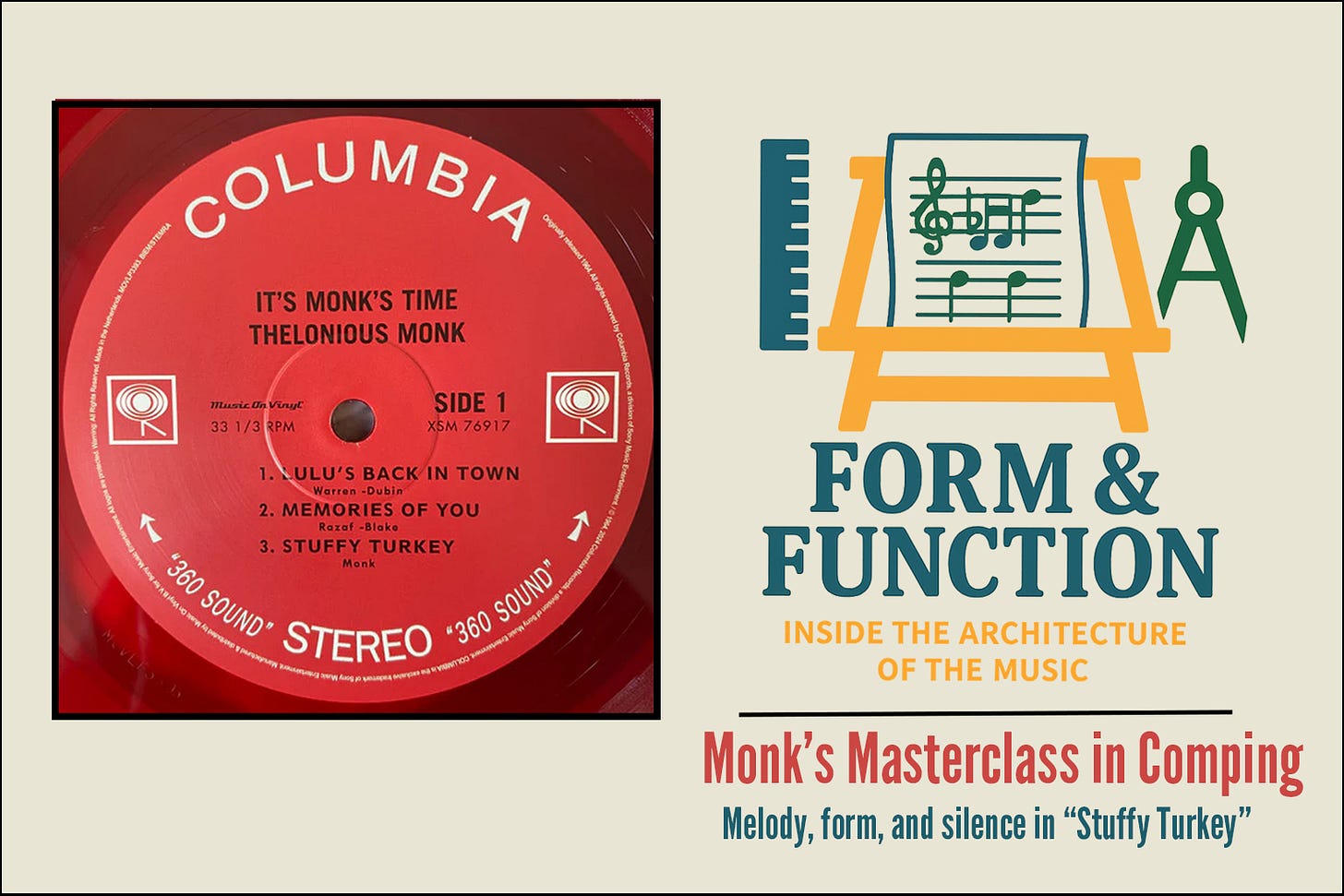

Monk's Masterclass in Comping

Melody, form, and silence in “Stuffy Turkey”

One of the unsung roles of piano playing is accompaniment. With all of the great piano virtuosos capable of breathtaking technical feats, it’s easy to forget that one of the foundations of piano playing in any genre is accompaniment. Not only does it accompany others, but it also accompanies itself. It is the ultimate accompanist instrument after all ca…