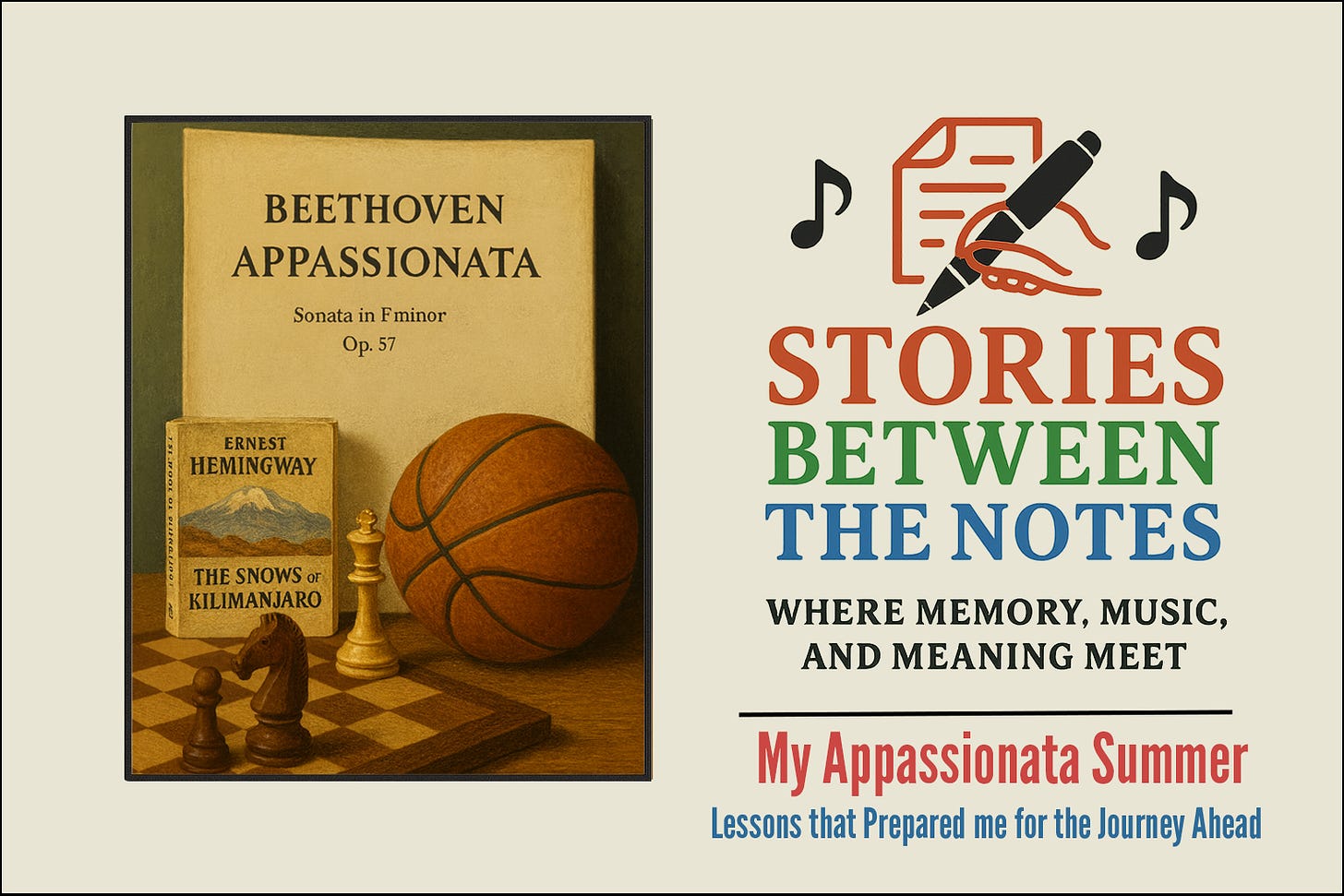

My Appasionata Summer

Beethoven, Hemingway, chess and the lessons that prepared me for my journey ahead

In the summer of 2010, while my family was in the midst of moving from New Jersey—where we had spent the past ten years—to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, I was given the chance to bid a proper farewell to the place of my adolescence. I would spend the summer in New York City, staying with Wynton Marsalis and studying one last time with my piano teacher of te…