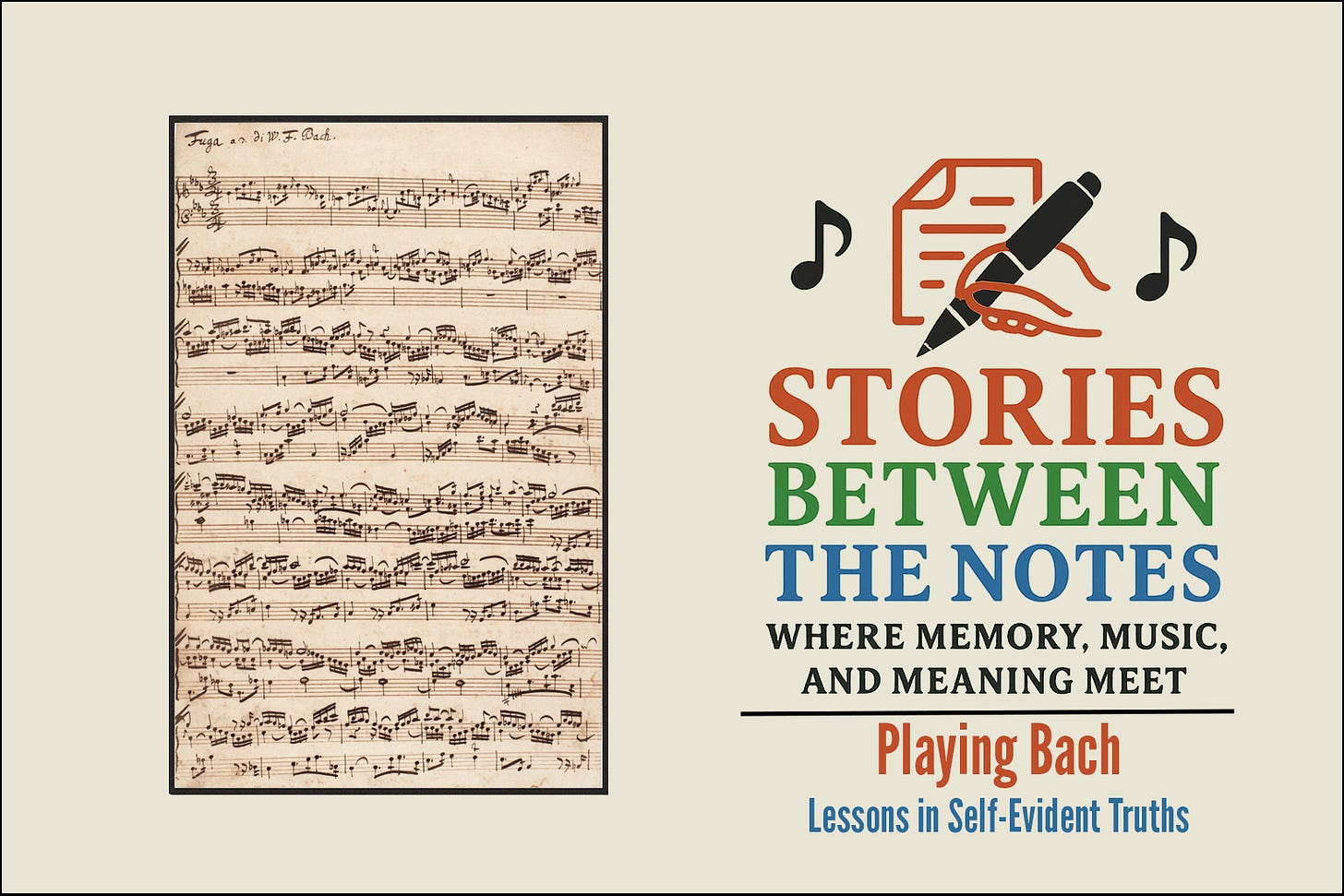

Playing Bach

Bach taught me the most self evident truths about piano playing

At the end of every year, when Spotify takes it upon itself to remind you of all the music you’ve listened to, there are two certainties: Future will be my top artist, and Johann Sebastian Bach will appear—often in multiple guises. Last year, in fact, Bach showed up three times in my top five: as Johann Sebastian Bach, the composer himself; Tilman Hopps…