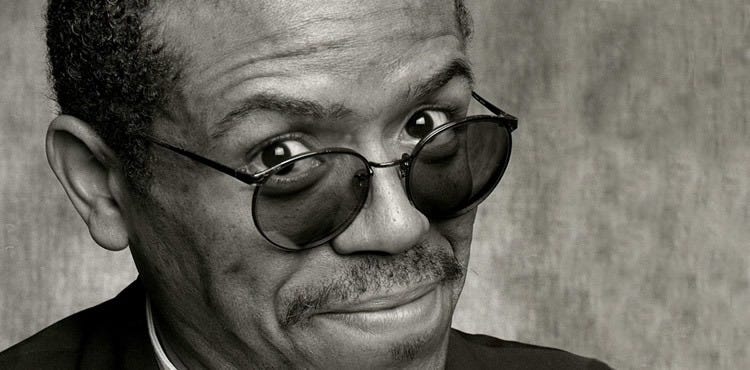

Wynton Marsalis: A Composer’s Retrospective — Black Codes (From the Underground): Part II

Between Miles and Trane: The Musical Influences on Black Codes

Editor’s Note

The first two articles in this series of each installment will be free to everyone. The complete series, including the exclusive unabridged interview with Wynton Marsalis, will only be available to paid subscribers.

Assembling a series like this takes months of interviews, research, and writing. If you’d like to journey with me through the entire project and support this type of in-depth music journalism, please consider signing up for a paid subscription.

When approaching musical analysis, there is always a temptation to go into notes, chords, and chord changes to explain the inner workings. While this approach to analysis has its uses and can be enlightening, it also has the effect of bringing a layer of abstraction to the understanding of the music. Chord changes for all the songs on this ablum are accessible through sheet music available on Wynton’s website and are useful for learning the music, though many of the jazz greats may beg to differ!

Though they can explain the “what” of the music and part of the “how” they do very little to explain the “why”. From my own experience with this album, I spent a good part of my middle school years transcribing the songs and learning to play them. When I would inevitably go to any of the other band members who knew these songs for the changes, I would always be met with a shrug, as many of them didn’t remember the changes. When I would ask Wynton, he would ask for my own interpretation of what the changes were before giving me the chord changes he wrote. It was at that age I found out how little the written changes did to enhance my understanding of the music. On the contrary, at that age their complexity deterred me from examining them any further.

When approaching this album as an adult, I began to glean insights from the music from simply listening and comprehinding things that my middle school self wasn’t able to understand. There are contextual aspects of music that can’t simply be explained with notes and chords. Wynton Marsalis’ bands in general are all very personnel driven. His music changes drastically depending on who he is writing for and who is playing on it. In this article I will take a look at the music through the lens of its central influences.

Between Miles and Trane

Whenever discussing the early career of Wynton Marsalis, especially around the time of Black Codes, there is almost always the invocation of Miles Davis and his Second Great Quintet as a major inspiration for the band. But in my conversation with Jeff “Tain” Watts, he brought up a debate within the band that was telling in terms of the influences present in the band’s approach to jazz.

“I think we were on a tour bus and there was a discussion of Coltrane’s band versus Miles’ band in the ‘60s. From Wynton’s standpoint, it was like Miles’ group was superior….Like Tony Williams, you can hear more of a rudimental type of playing and a type of velocity that’s associated with playing the drums from the European tradition very well….And maybe Herbie’s harmonic thing was something that was somehow deeper.”

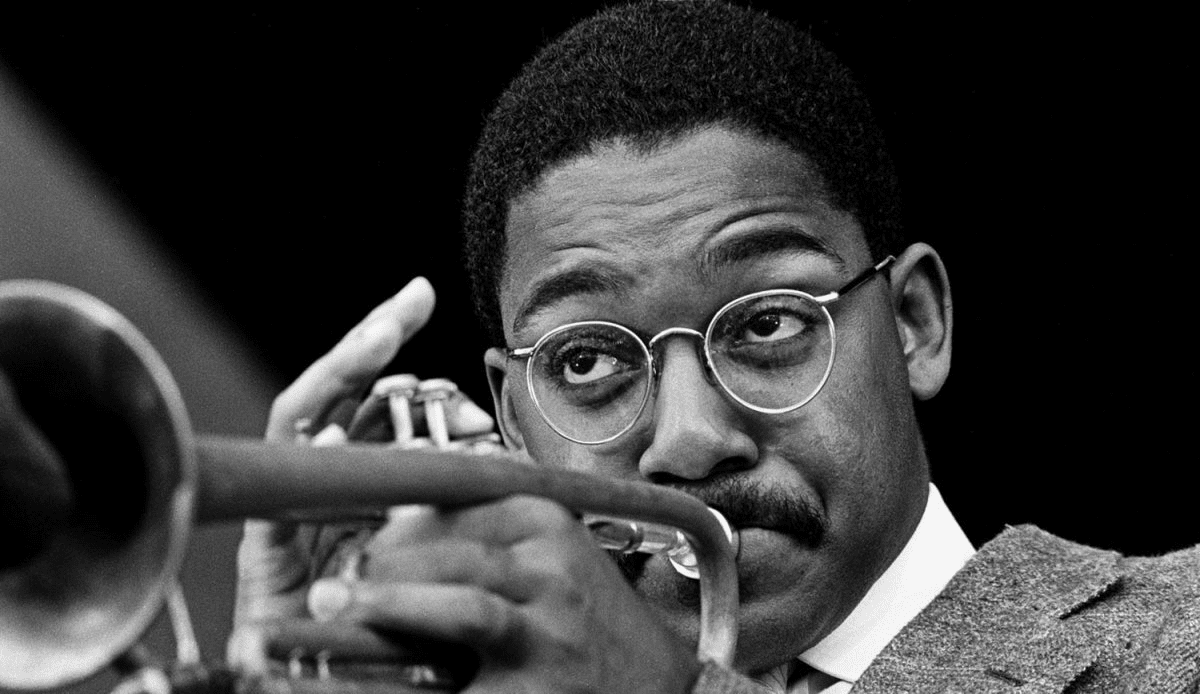

For Branford, this wasn’t as much of an ongoing debate as it was the formula for how the band should approach jazz.

“Trane’s band had a certain kind of emotional import that I thought was unique. And what I would talk to Tain about was that we would study the music that Miles and them did, because that was a certain kind of harmonic and intellectual freedom that’s quite astounding. But we needed to attack the music the way Trane’s band did. So it wasn’t about which band was better for me.”

When framed in the context of this ongoing debate within the band, Black Codes can be seen as an album at a crossroads between the formalism of Miles Davis and the intensity of John Coltrane. The velocity of Tony Williams vs the sheer swingingness of Elvin Jones. If those two different approaches to the avant-garde of the 1960s, could be brought together, that would become a roadmap toward doing something they believed to be new and fresh.

On a cursory listen, the influence of John Coltrane may not be obvious. I believe the key to Coltrane’s influence lies within the rhythm section. There was a certain intensity that the unit of Kenny Kirkland, Charnett Moffett, and Jeff Watts brought to every song. They would constantly push Wynton and Branford throughout their solos. Mondre Moffett, Charnett’s older brother, pointed out that with this rhythm section, you would end up places in your solo you would never expect to be.

In a song like “Delfeayo’s Dilemma” for example, notice how the intensity during their solos would gradually build up. Whether through Kenny Kirkland’s conversational comping, Charnett Moffett’s harmonic exploration, or Jeff Watt’s insatiable drive, throughout the course of a song, from solo to solo, the intensity would build.

The clearest example of a Coltrane-like song on the album would be Kenny Kirkland’s song “Chambers of Tain”. The song begins at a high level of intensity with the Afro-Cuban inspired groove and virtuosic melody, but it’s really the solos where the intensity goes through the roof. Note how much faster the song becomes between the beginning of Wynton’s solo and the point after Branford’s solo returns back to swing and Kenny Kirkland’s solo. Compare that to the intensity of swing behind McCoy Tyner’s solo in a tune like “Evolution” where his solo similarly comes last in the sequence of soloists.

If Coltrane’s influence is the spirit and attack of the music, then Miles’ influence is in the edifice that provide each song support. Whereas Coltrane’s band was trying to break down the barriers of jazz itself, Miles' band was trying to reconcile these avant-garde developments with the hard bop background the musicians in the band were coming from. Their approach to this was widely through creating approaches to form that would enable flexibility and exploration. In his book The Studio Recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, 1965-68, music theorist Keith Waters, regarding writes the following:

“These compositions also provided vigorous alternatives to standard-tune formal frameworks since they largely abandoned 32-bar AABA or ABAC chorus forms. Many were single-section works without bridges and without standard harmonic turnarounds, and the absence of internal formal divisions contributed to the group’s flexible and open sound…Melodically, too, the compositions’ reliance on short, memorable motives seemed to encourage highly motivic improvisation”

This influence of Miles Davis’ Quintet can be seen in the form and shape of the songs on Black Codes. Many of the songs on the albums were in some shape or form, an extended or modified blues form, so it makes sense that the songs would follow the mold of “single sections” with melodies composed of “short memorable motives”, given in a very rudimentary way, that is what the blues is.

“Delfeayo’s Dilemma”, “Phyrzzinian Man”, and “Chambers of Tain” are the most straightforward in this single section mold. Tain notes this specifically about the title song “Black Codes. “It’s got some compositional stuff in there, but then for the actual soloing is kind of like an extended blues form. It’s like a blues with a tag on it, some extra bars.” He partially attributed this influence to Wynton’s work with Herbie Hancock right before recording Black Codes, so for him, they as a band “were kind of obliged to have that type of probing quality to the music and try to extend that.”

Another idea inspired by Miles Davis’ band that allows for the flexibility in these songs is the use of musical devices as forms of communication. Rather than simply gesturing at bandmate to communicate, a specific motif is played. Tain explains:

We just started messing around with devices, and messing around with time, trying to extend what Miles and Mingus had done with time. Also there’s stuff like the device of having musical cues.

So maybe you would have a line from the tune that would signal you to either go to another tempo, or going to another section, or going to a vamp. And so I guess that’s kind of an extension of Miles Davis on his song “Paraphernalia” on Miles in the Sky. There’s kind of like examples of musical cues there.

So then how does that manifest itself in Wynton’s music, I asked.

Yeah, there’s a device like that on “Father Time”, he said. There’s a device like that of course on “Knozz-Moe-King”, just like a melody telling you to go to another section. On Kenny Kirkland’s tune, “Chambers of Tain”, there’s that type of device.

As Tain describes, the most obvious instances of these devices are the tags at the end of the solos which either indicates a shift to a groove or the end of the solo itself. This is most prominently seen in “Black Codes” and “Chambers of Tain”. This has the feel of a relay race with Wynton handing off the baton to Branford or Branford to Kenny Kirkland.

While countermelodies are a feature of Miles Second Great Quintet, this is something I would attribute more to the influence of Wayne Shorter within the band and his influence on Wynton compositionally.

The countermelodies in each song are as important to the identity of the songs as the melody. Without the countermelody, the melody of the song sounds incomplete. Take for example the recording of “Delfeayo’s Dilemma” from Black Codes and compare it to Wynton’s recording on Live from the Blues Alley where only Wynton takes the melody . One can’t help but feel Branford’s absence. Marcus Roberts makes up for this absence with his comping, soloing in between the breaks in the melody, and counterpoint of his own.

“Phyrzzinian Man” is the most involved in terms of counterpoint. Melody is played in parts by the trumpet, saxophone and piano, while the bass line lick is played by both the bass and piano. There are rhythmic hits interspersed throughout giving this song more of a big band arrangement feel.

A moment that seems a callback to Miles’ Quintet is the recapitulation of the melody at the end of “Delfeayo’s Dilemma”, where Tain plays a metrically modulated swing as a rhythmic counterpoint to the already rhythmically rich melody. This recalls the same kind of metrically modulated swing Tony Williams played at the end of “Footprints”. This gesture, though mostly a clever moment at the end of a song, would become more sophisticated on “Live at the Blues Alley” where Watts would define entire forms rhythmically, most prominently in “Autumn Leaves”. This evolution of metric modulations into rhythmic forms would have been an interesting thread to see evolve within Wynton’s music as well as the music of Tain.

All of these musical ideas present in Black Codes would be ideas that Wynton would develop throughout his career. If one listens to his septet writing, extended forms, contrapuntal melodies and interludes become prominent features, utilized with great sophistication. Wynton’s big band writing is exceptionally dense because of his penchant for involved counterpoint.

What I believe makes this album special though, is how it sits at the crossroads of two different notions of freedom. The Miles Davis Second Quintet consciously toed the line between the avant-garde of the time which had been gaining steam throughout the 1960s, and the traditional more accessible forms of instrumental jazz that Miles was known for. Herbie even referred to the way they played as “controlled freedom”. On the other end, John Coltrane was seeking to unmoor himself from all limitations within the music, absolute freedom.

The framework of Black Codes belies the influence of Miles Davis but the intensity and reckless abandon that each musician would bring to each song would be John Coltrane’s lasting influence. To understand the energies and synergies in the band, it is important to take a look at the personnel of the band and the contributions each musician brought to the music.

Next Week in Part III, I examine the chemistry of the quintet itself, the contrasting and symbiotic relationship between Wynton and Branford, and the extraordinary rhythm section of teenage prodigy Charnett Moffett, veteran mastermind Kenny Kirkland, and the polyrhythmic Jeff “Tain” Watts. Drawing on recollections from Mondre Moffett, Branford, and Tain, this section reveals how the band embodied a concept sometimes referred to as “burnout”, a balance of personal freedom and collective participation that evolved the innovations of the 1960s into something entirely new.

This analysis of Miles' controlled freedom vs Trane's absolute freedom is absolutley brilliant. The way you framed Black Codes as a crossroads between these two philosophies made me rethink how i listen to that whole era. Thats such a useful lens for understanding not just Wynton but like any artist navigating tradition and experimentation. Had a similiar revelation when I first really listened to Chambers of Tain.

This article comes at the perfect time. Building on the first part, your insight into the 'why' of music is truly thought provoking.