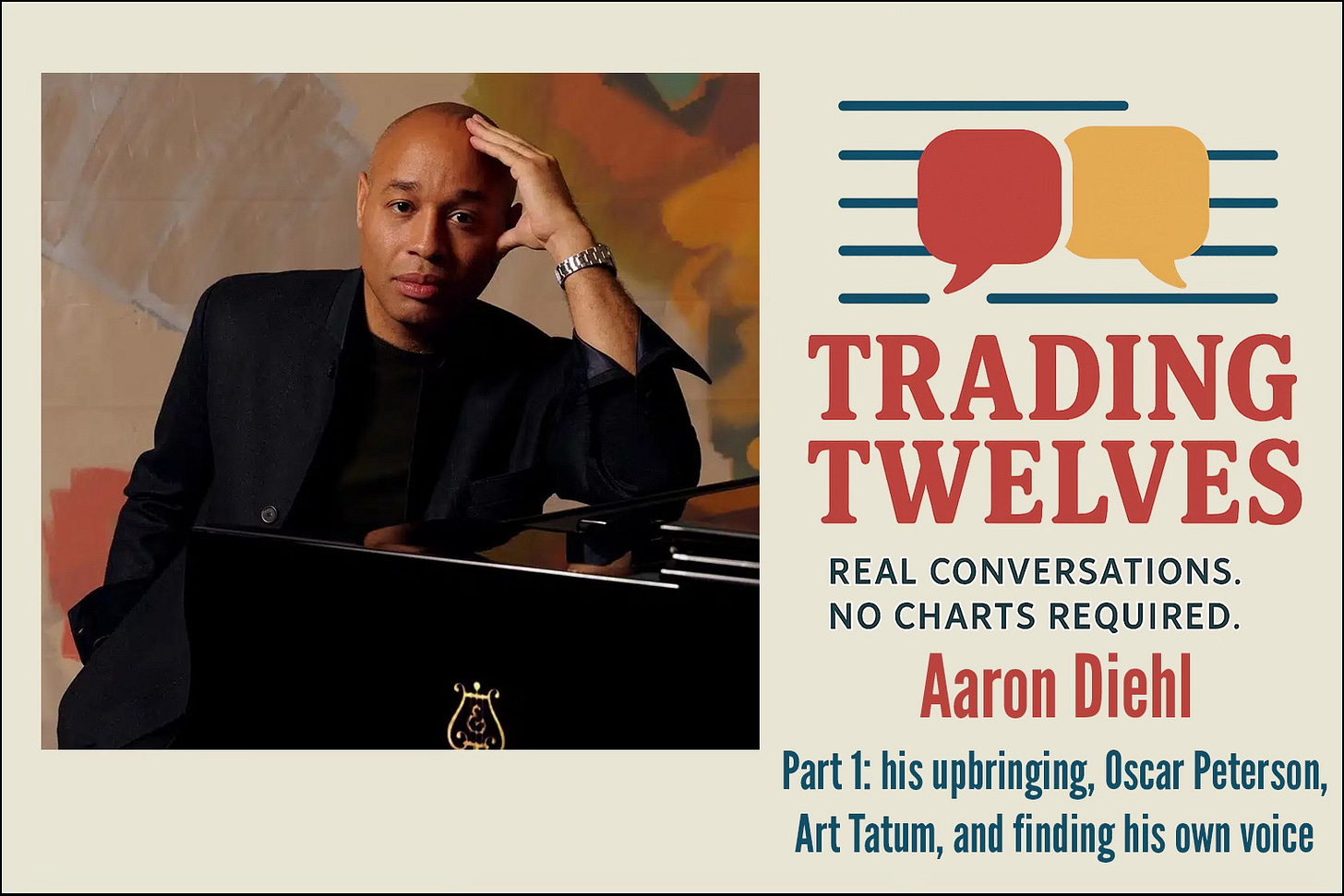

A Conversation with Aaron Diehl Part 1

Pianist Aaron Diehl discusses his upbringing, Oscar Peterson, Art Tatum, and finding your own voice in jazz

When I was a child, not long after I first met Marcus Roberts, I heard a rumor about an eighteen-year-old pianist at Juilliard who could play Art Tatum’s rendition of “Tiger Rag”. To me, anyone who could play stride at that level bordered on mythical. That pianist turned out to be Aaron Diehl.

Years later, after we had gotten to know each other, Aaron i…