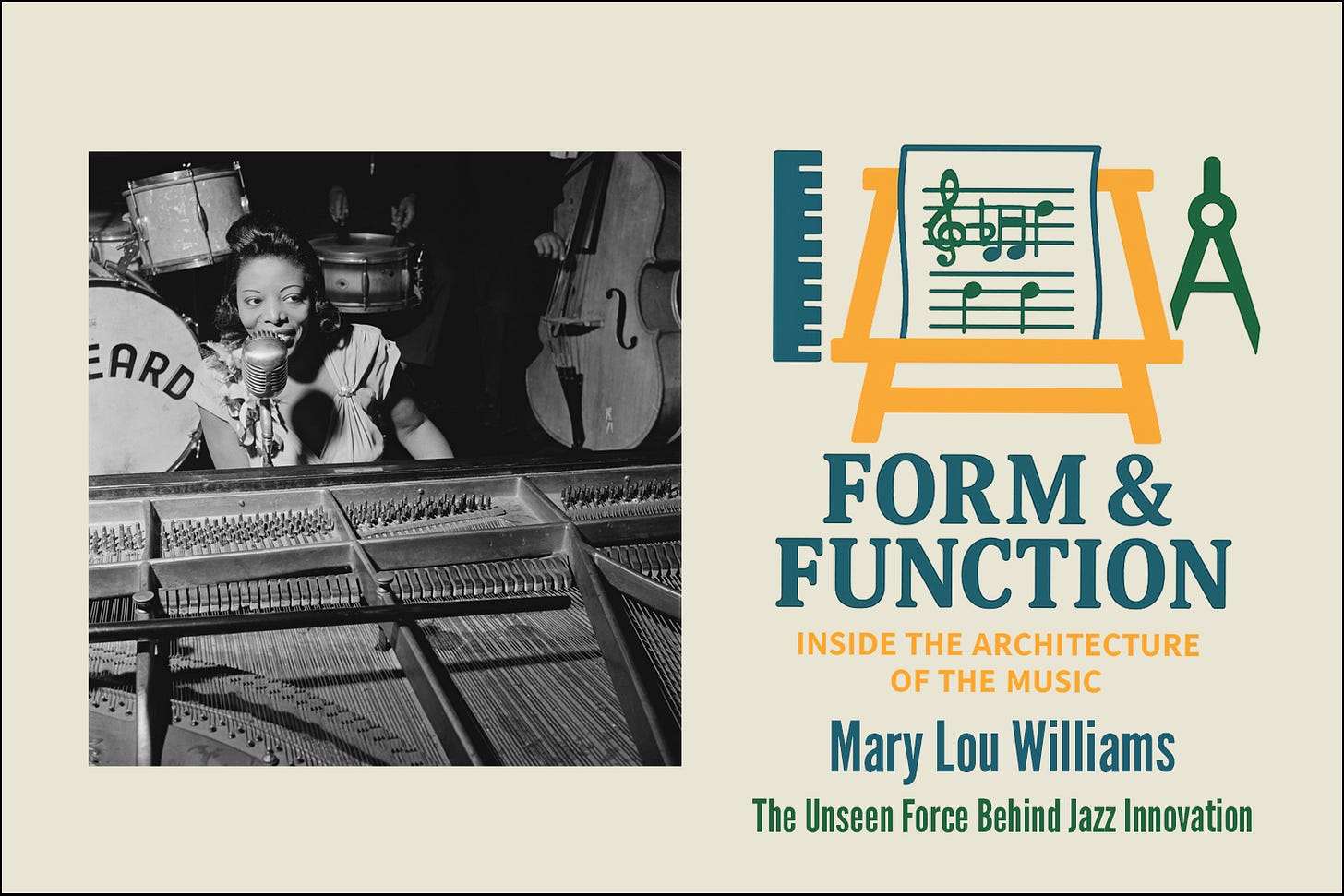

Mary Lou Williams: The Unseen Force Behind Jazz Innovation

How Mary Lou Williams Bridged Eras, Mentored Innovators, and Re-shaped Jazz History

Mary Lou Williams was a figure whose impact is felt immensely in jazz history, yet too often overlooked, partly because of her gender, and partly because the nature of her work resists easy categorization. She was the connective tissue between the stride pianists of the 1920s and the bebop innovators of the 1940s, a musician whose evolving harmonic lang…