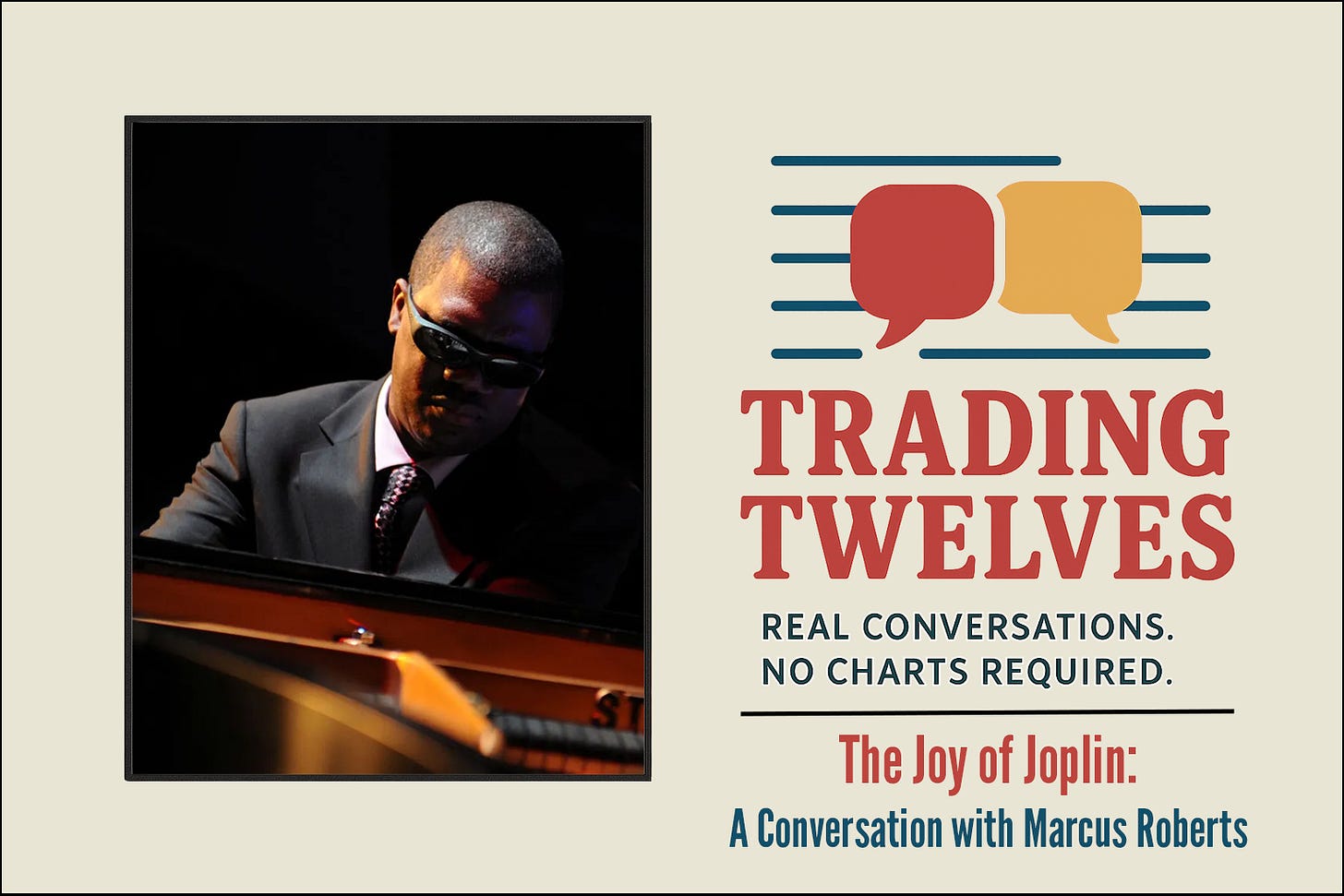

The Joy of Joplin: A Conversation with Marcus Roberts

Acclaimed composer, pianist and educator Marcus Roberts on his relationship with ragtime and stride piano

In my previous post, I discussed how I met Marcus Roberts and how he has long been an important mentor of mine since I was a child. Over the years I’ve had the opportunity to have conversations and lessons with him that have been invaluable to my development as a musician. I’m grateful that he took the time to sit down and speak with me for this piece a…