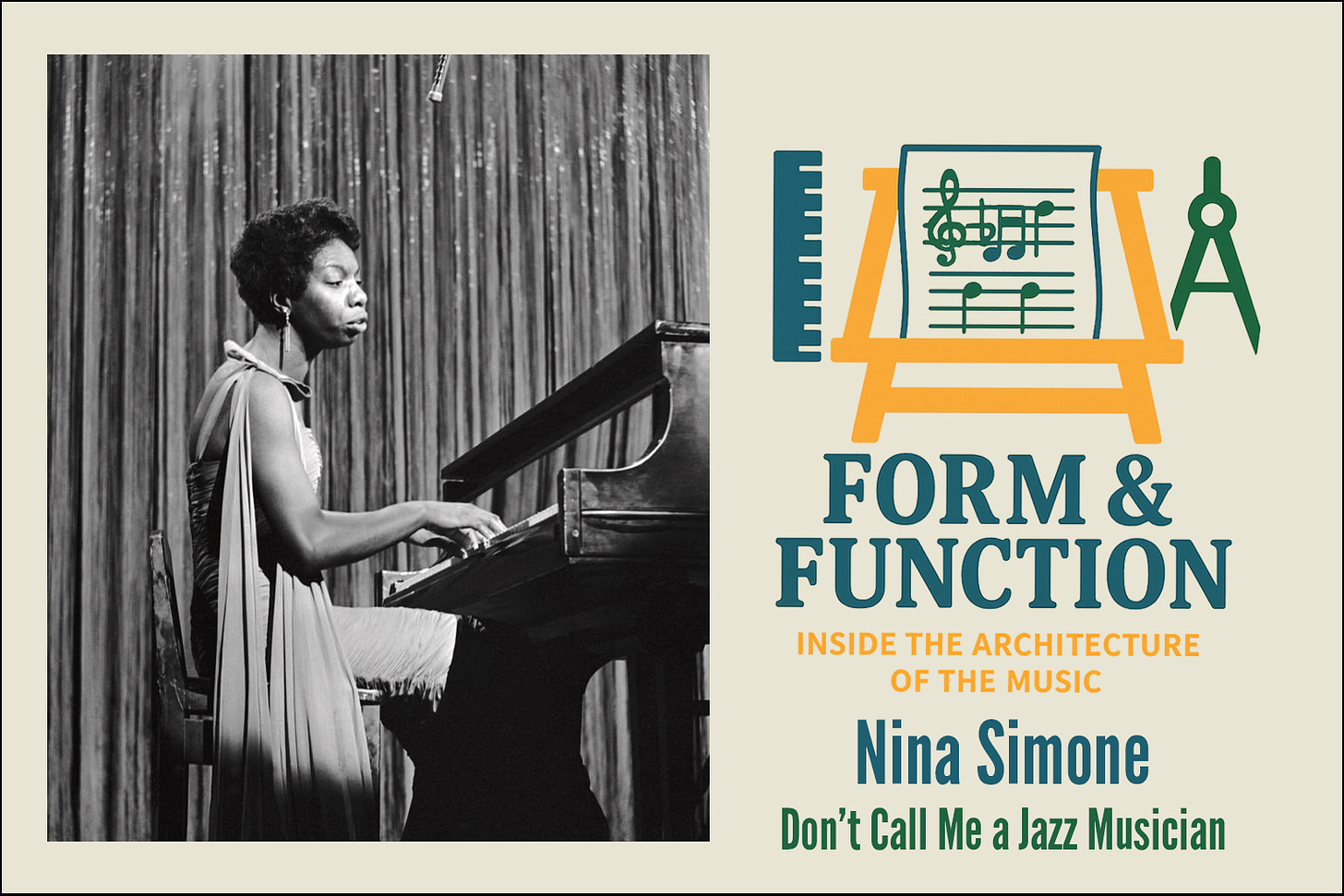

Nina Simone: Don’t Call Me a Jazz Musician

How a Classical Pianist Revived Classical Improvisation in Her “Black Classical Music”

Nina Simone is best known as a singer, her voice inseparable from songs like “Feeling Good” and “I Put a Spell on You.” But before she ever sang professionally, she was a pianist, and it’s in her piano playing that the full depth of her musical vision reveals itself.

On her debut album, Little Girl Blue, she begins the opening song, “Mood Indigo,” with a clear homage to the song’s composer, Duke Ellington, with her voicing, phrasing, and touch. But then something quite curious happens. Simone breaks into two-part baroque counterpoint with the direction, drive, and drama as compelling as any two-part invention or movement of a partita. And then, right at the highest point, she flows back into her Duke Ellington sound, wrapping up this astounding introduction.

Hearing Simone improvise in two distinct voices brought me back to a question I’d had since I first heard Marcus Roberts improvise a full walking bass beneath his right-hand solo on “Cherokee.” Clearly, nothing in jazz prevented a pianist from playing contrapuntally. So why didn’t more players explore it? Simone’s counterpoint, though, sounded different. It was clearly within the baroque style of counterpoint, but somehow it sounded like it belonged over “Mood Indigo.”

When people discuss Nina Simone and her background in classical music, the conversation inevitably turns to Johann Sebastian Bach. Simone had such a deep love and understanding of Bach that she could seamlessly incorporate music in his style into a jazz idiom.

“When you play Bach’s music you have to understand that he’s a mathematician and all the notes you play add up to something–they make sense. They always add up to climaxes, like ocean waves getting bigger and bigger until after a while when so many waves have gathered you have a great storm. Each note you play is connected to the next note, and every note has to be executed perfectly or the whole effect is lost.

For much of her early life, Simone, who was originally named Eunice Kathleen Waymon, trained to become a classical pianist. In the summer of 1950, she attended Juilliard School of Music as a student of Carl Friedberg while preparing for her audition for the Curtis Institute, the top institution for classical music in the country. Though she was confident in her chances of being accepted and expected a scholarship, she was rejected. Simone contended that the decision not to admit her was racially motivated, though the truth of the matter remains ambiguous.

Following her rejection, she studied privately with Vladimir Sokoloff, who would have been her teacher had she gotten into Curtis. He remembered her as a musician of real ability and discipline, and it was in his studio that he first heard her improvise in a jazz style. He even suggested she consider pursuing jazz professionally. Simone pushed back, saying her first love was classical music and that she wanted to be a concert pianist.

What eventually pulled her toward the jazz world wasn’t a change in her artistic outlook, but an economic motivation. She was teaching piano for income, and when she learned that one of her students was making twice her teaching rate playing in an Atlantic City bar, she decided to try it herself. To keep her devoutly religious mother from finding out that she was playing at a “seedy little bar where old guys go to huddle over a drink and fall asleep,” she performed under the name Nina Simone. But there was another condition to keeping the job: the bar owner insisted she sing as well as play.

Simone had never sung professionally before, but she needed the money, so she added her voice to her performances. What began as economic necessity became something transformative. Jazz, at the beginning, wasn’t her chosen path, and singing wasn’t either. But both became the space where her classical training, her ear, and her sense of identity could converge into something entirely her own.

Nina Simone achieved this synthesis of jazz and classical music not by combining styles, but by drawing on the shared tradition of improvisation that once united them. This aspect of Simone’s playing wasn’t just a novelty or a gimmick, but an organic synthesis of her training in a classical tradition with her love of black American music such as gospel, blues, and jazz.

Listening to Simone play got me thinking about the relationship between jazz and classical music. As a black composer and pianist raised in both traditions, I had long wrestled with how to bring them together in my own work. Early on I tried combining their languages directly, but gradually I began searching for a more organic synthesis.

When I was writing the piece J-Walking, for the pianist Aaron Diehl, I came to the realization that the key to the relationship between jazz and classical music was improvisation. In that piece, I sought to blur the line between what was improvised and what was written, utilizing Aaron Diehl’s mastery of both jazz and classical piano.

Improvisation is at the core of the relationship between jazz and classical music. Like jazz, improvisation was once a central part of the traditions and pedagogy of classical music. Many of the great composers such as Bach, Mozart, Beethoven were master improvisers. In their time, it was an expectation. To enter esteemed institutions like the Paris Conservatoire, one had to improvise a fugue on a given subject as part of the exam. With her playing, Simone was tapping into this tradition.

Classical music has also played a part in the history and tradition of jazz. Many jazz pianists have had a background in classical music, which underpinned their improvisational facility. Pianists from as early as Scott Joplin, Luckey Roberts, and Jelly Roll Morton studied classical music and actively incorporated it into their writing. Joplin considered himself a classical musician and ragtime a form of classical music. If one listens to recordings of Luckey Roberts, one can even hear popular nineteenth-century virtuosic figures such as the three-handed effect pioneered by Sigismond Thalberg and famously appropriated by Franz Liszt.

Many of the great jazz pianists of the 20th century also came from a background in classical music, such as Art Tatum, Mary Lou Williams, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Phineas Newborn, and Oscar Peterson. The main difference between these pianists and their predecessors was how their classical music background informed their jazz playing. Rather than appropriating the virtuoso language of the nineteenth century, these pianists used the facility that classical music gave them to deepen the virtuosity and flair of their jazz improvisation, even going so far as to create their own personal techniques. Take, for example, Art Tatum’s famous improvisation over the Chopin Waltz in C-sharp minor. Despite his playing a classical piece, it still sounds like vintage Art Tatum, as if it were any other jazz piece.

The traditions and pedagogy of classical music underwent a similar shift in the 19th and 20th centuries as conservatories became the main institutions for studying music rather than churches or apprenticeships. A codification process took place as the music moved to conservatories, and improvisation, a skill that cannot be taught in classrooms, fell out of the tradition. I remember once when my father asked my piano teacher, Ms. Emine, to improvise a blues, she politely declined, suggesting her improvisation would just sound like Bach or Chopin.

Like my piano teacher Ms. Emine, when Simone improvised, she indeed did sound like Bach. But Simone understood both mediums so well that she could weave original baroque counterpoint over jazz chord changes and make it feel as natural as if Bach had intended his music to be played over swing. In a way, Simone gives us a small insight into what it must have been like to see someone like Bach bring a sense of spontaneity and wonder to fugues, canons, and inventions.

Nina Simone is best understood not as a jazz pianist or jazz musician who played classical music, which was how she was often framed, but rather as a classical musician playing black music. She was often irked by the suggestion that she was a jazz musician or jazz singer.

“To most white people, jazz means black and jazz means dirt and that’s not what I play. I play black classical music. That’s why I don’t like the term “jazz,” and Duke Ellington didn’t either - it’s a term that’s simply used to identify black people.

Simone’s phrase “black classical music” is essential to understanding her artistic philosophy. She refused to draw hard lines between the black American musical inheritance and the European classical canon. Instead, she treated them as parts of a single, continuous tradition. The term doesn’t subordinate one to the other, but rather elevates both by insisting they belong in the same conversation, demanding the same seriousness, study, and virtuosity.

In Simone’s era, labels such as “jazz” were often used to separate black musicians from the category of “classical” musicians, creating the illusion of two incompatible worlds. But such distinctions obscure the deeper reality that musicians across these traditions are expressing themselves through their specific tradition. Jazz is an American art form, one that grew from the same broader Western harmonic and pianistic tradition as classical music.

At the highest levels, the difference between jazz and classical musicians is not talent or rigor. It is simply the tradition in which they specialize. Simone’s work makes this undeniable.

Good piece, Wynton!